Curating Assertions¶

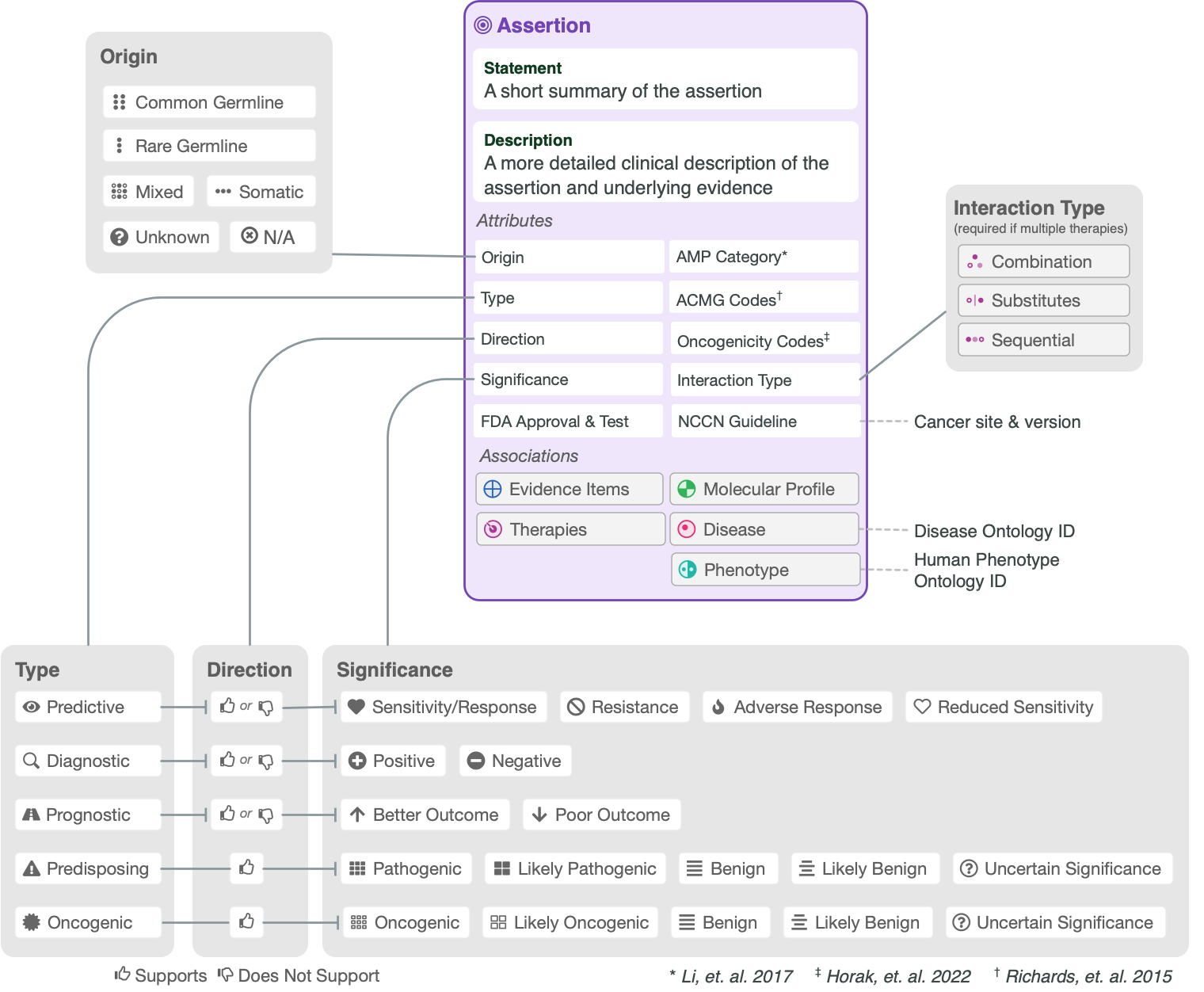

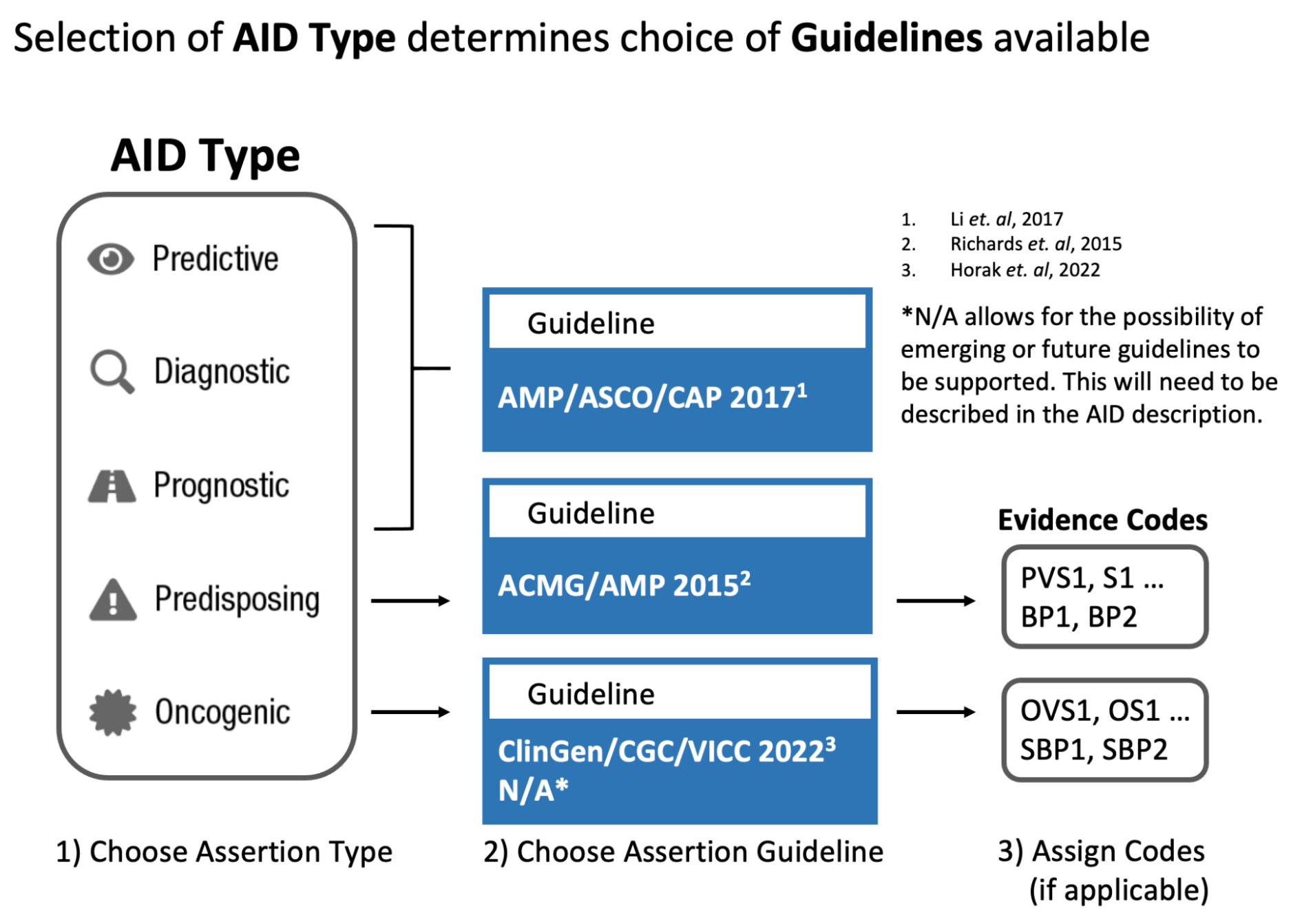

The CIViC Assertion (AID) functions as a summary of clinical evidence for a Molecular Profile (variant), disease and specific predictive (therapeutic), prognostic, diagnostic or predisposing clinical significance supported by Evidence Items (EIDs) appearing in CIViC, along with evidence drawn from other sources, such as databases of variant population frequency. The Assertion is designed to incorporate information from practice guidelines (e.g., NCCN) and also integrates widely adopted clinical tiering systems into structured fields, including:

AMP-ASCO-CAP guidelines (Li et al. 2017) for clinical tiering of somatic variants (Predictive, Prognostic, Diagnostic assertions).

ClinGen/CGC/VICC SOP (Horak et al. 2022) for classification of somatic variant oncogenicity (Oncogenic assertions).

ACMG-AMP guidelines (Richards et al. 2015) for classification of germline variant pathogenicity (Predisposing assertions).

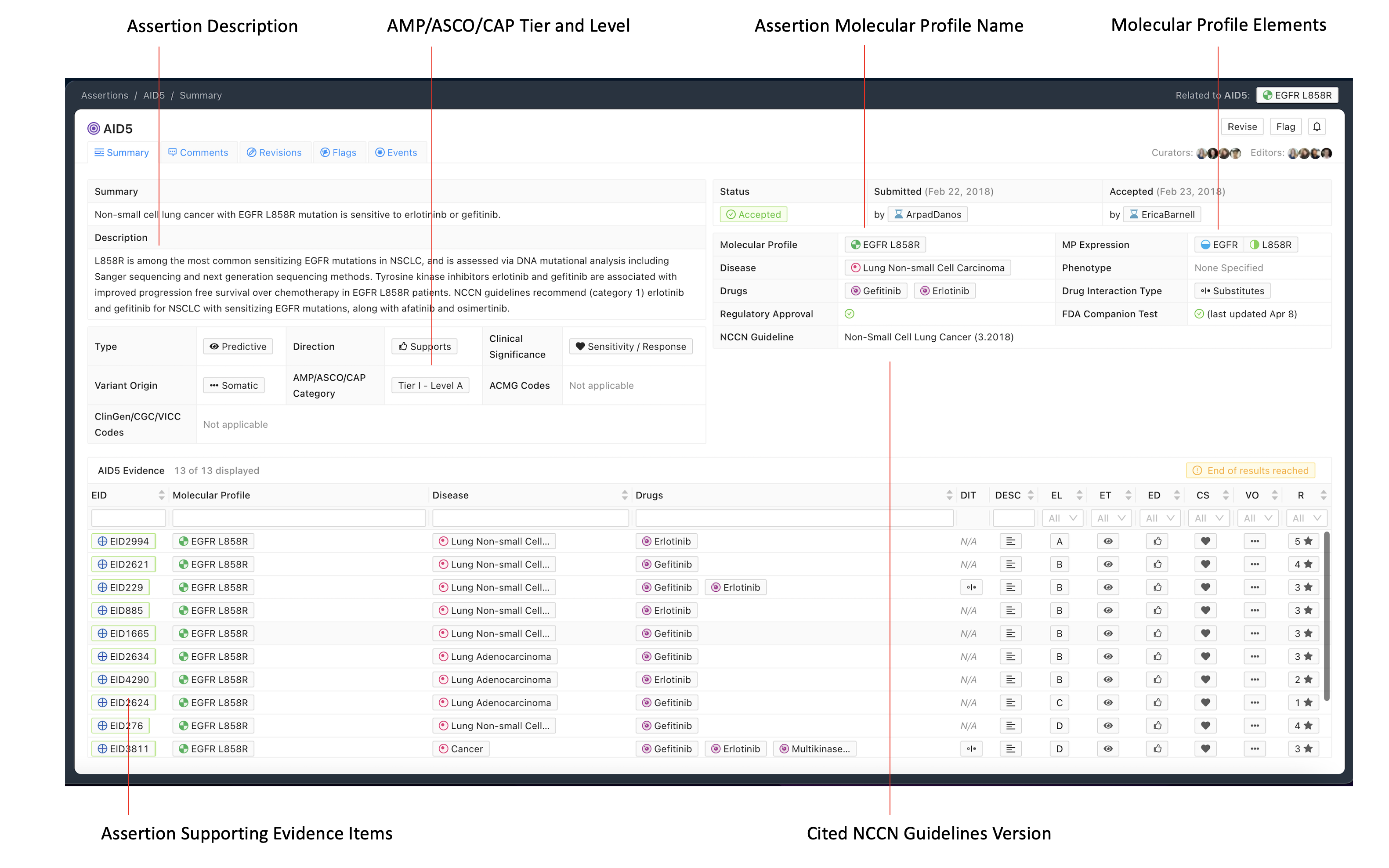

The Assertion contains a one sentence Assertion Summary which states the specific Molecular Profile (MP), disease, and significance with therapy if applicable (e.g. “Non-small cell lung cancer with EGFR L858R mutation is sensitive to erlotinib or gefitinib” in Figure 1 above).

Beneath the Summary is the Assertion Description, which contains background clinical information specific to the Molecular Profile (MP), disease, and predictive (therapeutic), prognostic, diagnostic or predisposing significance. EIDs supporting the Assertion’s clinical significance may be listed in this description, and referenced using CURIE identifiers (e.g., civic:EID1234). For Assertions with a higher AMP-ASCO-CAP Tier (Li et al. 2017), the Assertion Description section should list major practice guidelines and approvals associated with the clinical significance. For therapies, this may contain a brief restatement of guideline recommended treatment line and cancer stage (e.g. “NCCN guidelines recommend (category 1) erlotinib and gefitinib for NSCLC with sensitizing EGFR mutations, along with afatinib and osimertinib.” in Figure 1)

The CIViC Assertion is supported by CIViC Evidence Items (EIDs) which describe the same Molecular Profile, disease and significance as the given Assertion. The Assertion may also be supported by EIDs written for a more generalized MP. For example an Assertion regarding erlotinib sensitivity of EGFR L858R lung cancer may be supported in part by EIDs written for a more general MP such as EGFR Mutation which utilizes the categorical/bucket variant “Mutation”. Note that an Assertion for a specific MP such as EGFR L858R cannot be entirely supported by EIDs based on more general variant types such as Mutation, and requires some supporting EIDs Molecular Profiles based on the same specific variant type. Similar principles apply to the Disease, where an Assertion for a specific disease type may in part be supported by EIDs for a more general disease class (e.g. Cancer, DOID 162). Note that cited guidelines should be disease specific.

A sufficient amount of evidence should be added to an Assertion so that the collection of Evidence Items represents the ‘state of the field’ for the Disease, Molecular Profile, and Clinical Significance. As new evidence emerges which is relevant to a CIViC MP with an accepted Assertion, then additional Evidence Items can be curated from this new evidence, and added to the Supporting EIDs for the existing Assertion, potentially changing its ACMG-AMP classification or AMP-ASCO-CAP Tier and Level.

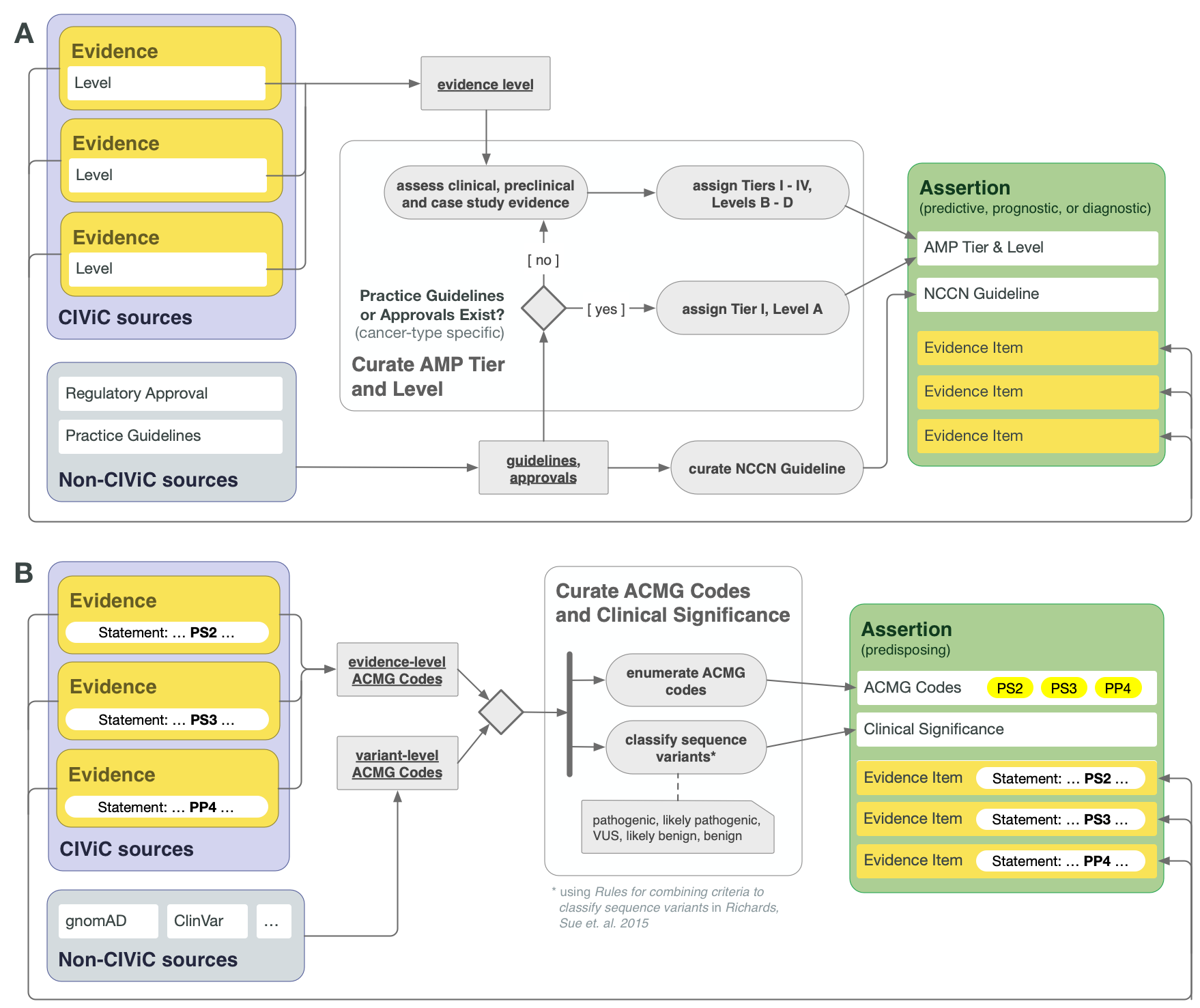

CIViC Assertions summarize a collection of Evidence Items, along with certain evidence drawn from sources other than publications or meeting abstracts, which together reflect the state of literature and clinical knowledge for the given Molecular Profile and disease. For Assertion Types dealing with actionable clinical information (Predictive/Therapeutic, Prognostic, or Diagnostic), AMP-ASCO-CAP 2017 guidelines are followed to associate the Assertion with an AMP Tier and Level. For the highest tier Assertions, this involves consideration of practice guidelines as well as regulatory approvals for drug use in the specific context of the variant and disease. In the absence of explicit regulatory or practice guidelines, the supporting clinical and case study Evidence Items should be used to guide application of AMP Tier and Level (Figure 4A).

Lower AMP-ASCO-CAP Tier Assertions can be written for Molecular Profiles that are not supported by practice guidelines or extensive clinical evidence, relying on case study and preclinical data. The supporting EIDs should reflect the state of the field regarding the emerging knowledge in such cases, and AMP Tier should be assigned based on the curator and editor’s overviews of the field. It is recommended to consult recent reviews in this case.

CIViC Predisposing Assertions utilize ACMG-AMP 2015 guidelines to generate a 5-tier pathogenicity valuation for a variant in a given disease context, which is supported by a collection of CIViC Evidence Items, along with other data. ACMG evidence codes for an Assertion are supplied by a collection of supporting CIViC Evidence Items (e.g., PP1 from co-segregation data available in a specific publication), and additionally are derived from variant data (e.g., PM2 from population databases such as gnomAD). ACMG evidence codes are then combined at the Assertion level to generate a disease-specific pathogenicity classification for the Assertion (Figure 4B and Figure 8). CIViC Oncogenic Assertions work in a very analagous way but follow the ClinGen-CGC-VICC 2022 SOP.

Other guidelines that curators should keep in mind include:

While the body of supporting Evidence Items may be derived from studies with differing patient populations with regard to stage and line of treatment, as well as preclinical studies in disease models, the Assertion may describe more specific disease context based on reading of practice guidelines (e.g. NCCN etc), and any such descriptions added to the Assertion should explicitly cite the practice guidelines as the source.

Generally, even when the supporting Evidence Items exactly line up with the treatment context described in the Assertion, practice guidelines may be summarized in the Assertion description, including disease stage, line of treatment (e.g., first line, salvage), and this information should be clearly labeled as being derived from published guidelines, and those guidelines explicitly cited.

Approved companion diagnostics (e.g. Vysis Break-Apart Fish diagnostic for ALK-fusions) may be listed in the Assertion Description.

All Evidence Items relevant to the Assertion should be associated to it, even if they disagree with the Assertion Summary. Disagreements can be discussed in the Assertion Description section and the rationale for discounting discrepant evidence should be recounted.

The CIViC Assertion contains specific Variant Origin fields which are filled out during Assertion creation. It is possible for some EIDs in the supporting evidence to have a different Variant Origin than that in the Assertion, but the Assertion should contain substantial support from Evidence Items with the same Variant Origin as in the Assertion.

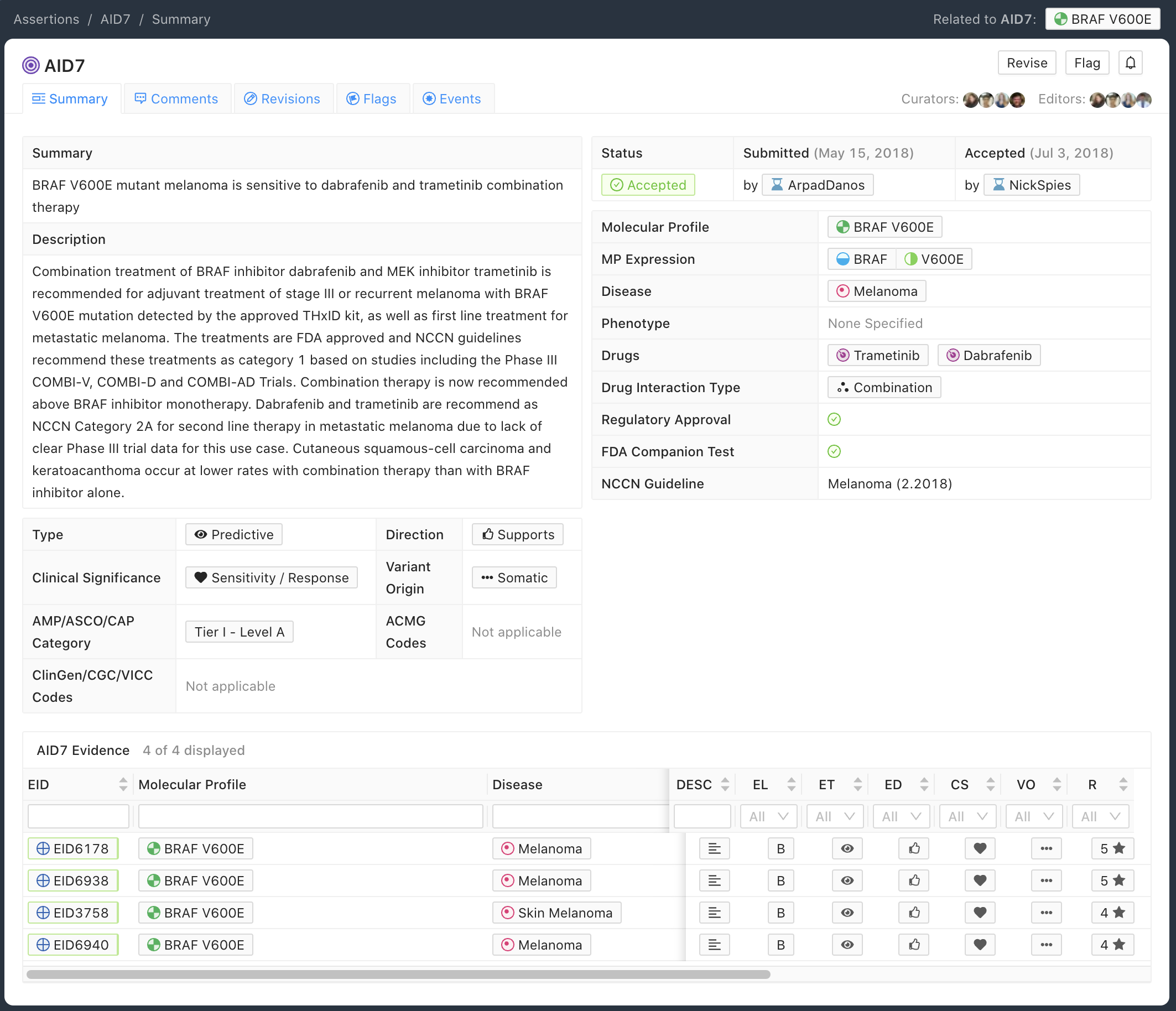

Predictive Assertions¶

The Predictive Assertion screenshot below (Figure 5) describes that BRAF V600E confers sensitivity to combination therapy of dabrafenib and trametinib for patients with melanoma. The AMP-ASCO-CAP Category is Tier I - Level A for this variant, disease and drug sensitivity assertion. The high AMP-ASCO-CAP Tier is a consequence of the presence of this Molecular Profile and treatment in the Melanoma NCCN Guidelines (v2.2018).

Curation Practices for Predictive Assertions¶

Predictive Assertions are generally associated with Molecular Profiles based on somatic variants. Still some germline variants may have pharmacogenomic properties that predict an adverse response to a treatment. In these cases, Predictive Evidence Items and an Assertion can be created for MPs based on these types of germline variants, with the Significance being Supports Adverse Response.

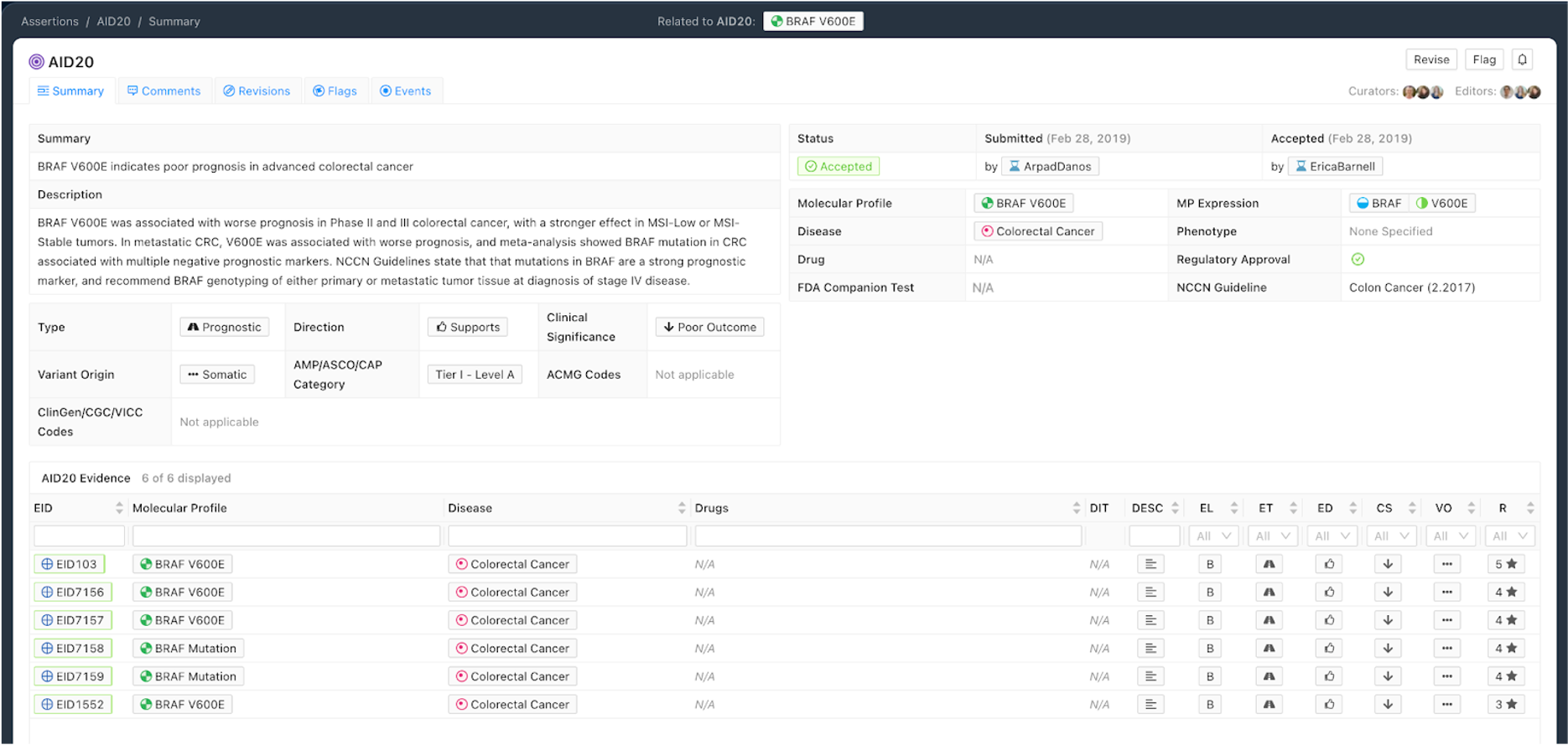

Prognostic Assertions¶

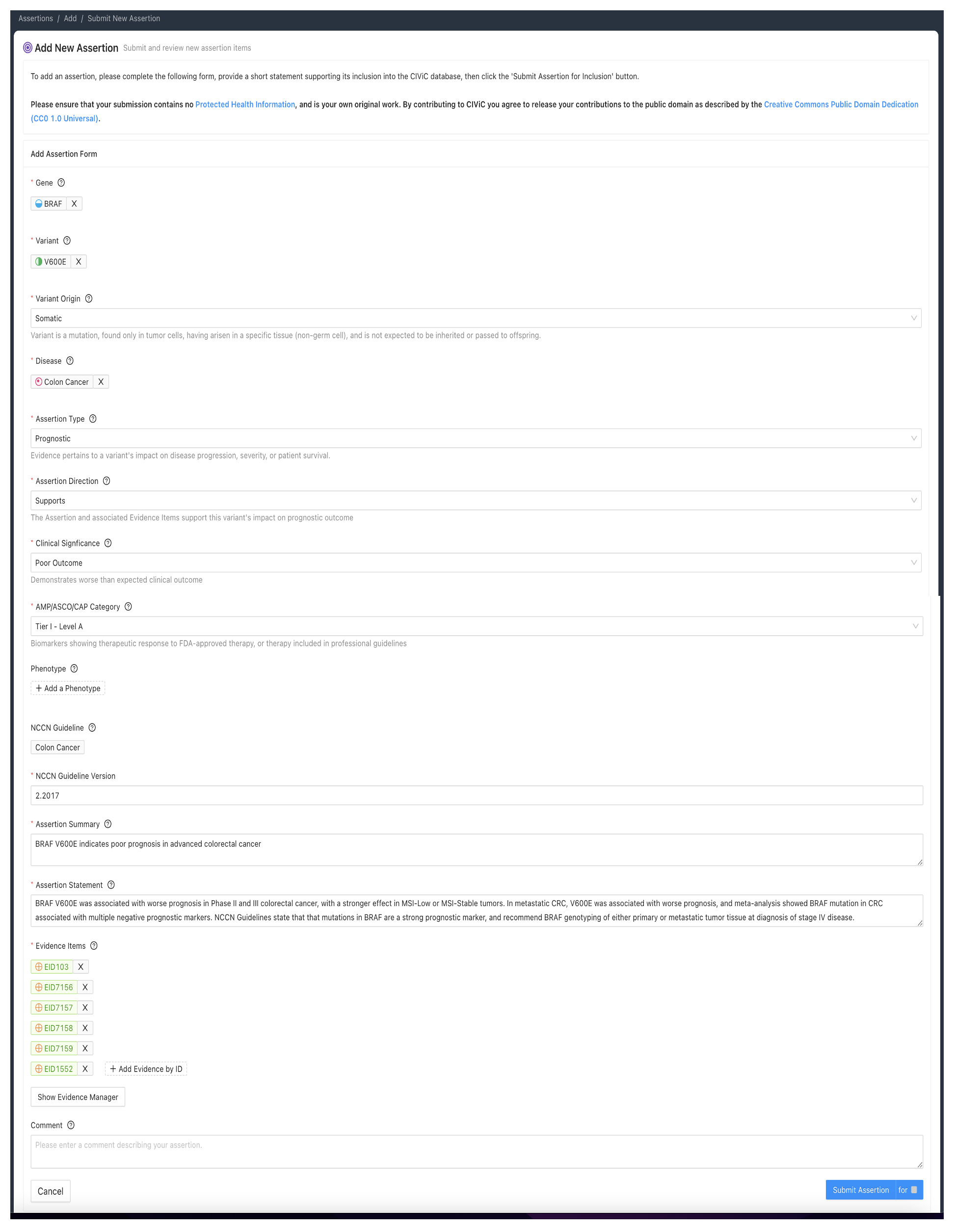

Figure 6 shows a Prognostic Assertion with an exemplary Assertion Summary and Assertion Description. In this example, the Assertion describes that the BRAF V600E Molecular Profile confers poor outcome for patients with colorectal cancer. This variant is listed in the NCCN Guidelines for colorectal cancer (v2.2017), and falls under the Tier I - Level A AMP category.

Curation Practices for Prognostic Assertions¶

Prognostic Evidence Items in CIViC describe a Molecular Profile (MP) being associated with better or worse patient outcome in a general manner, independent of any specific treatment. Evidence should show better or worse outcome in the presence of the MP, ideally under different treatment regimes and also in untreated cases if such data is available. Therefore, a larger collection of evidence showing similar prognostic outcomes under a range of different treatment or untreated regimes creates a stronger Prognostic Assertion.

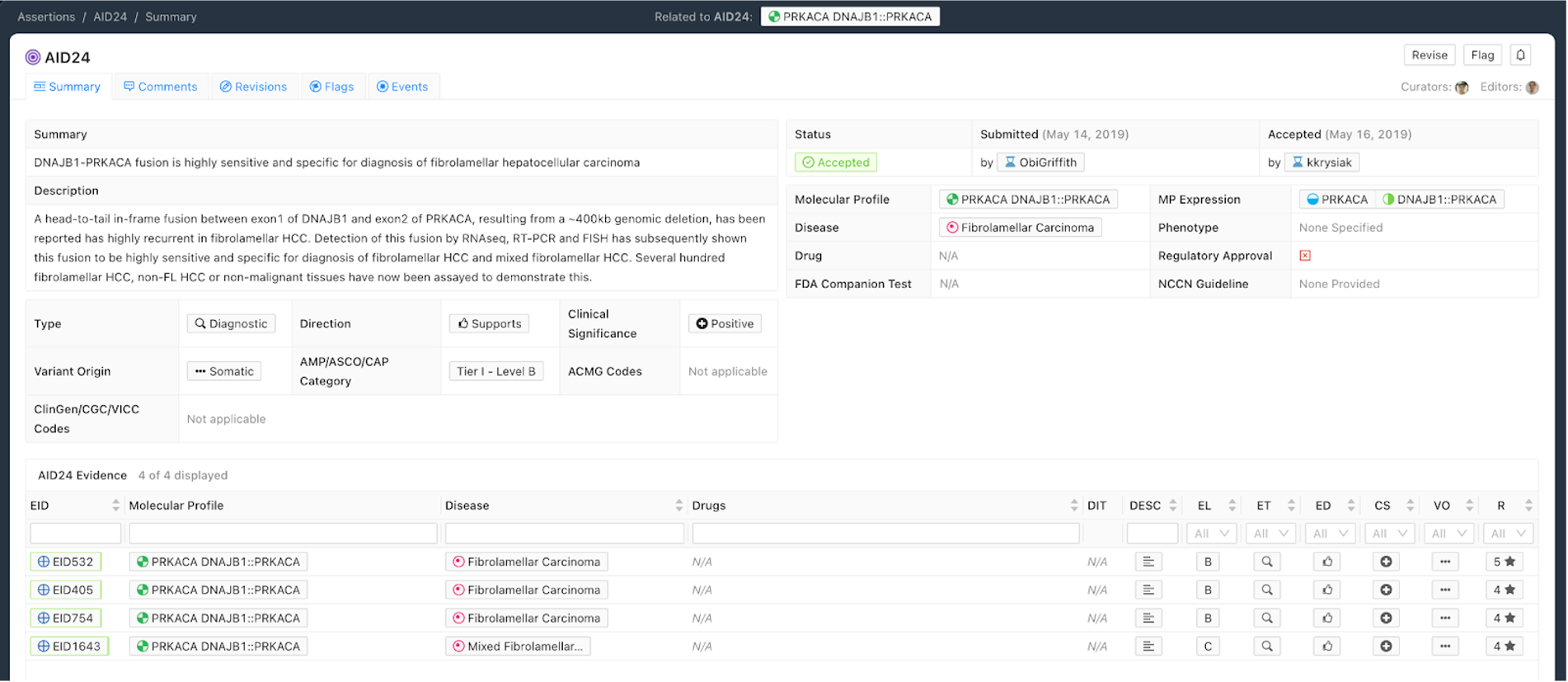

Diagnostic Assertions¶

Figure 7 shows an example of a Diagnostic Assertion with an exemplary Assertion Summary and Assertion Description. In this example, the Assertion describes how an in-frame fusion between DNAJB1 and PRKACA can be used to diagnose a specific subtype of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Presence of this fusion can be used to clarify that the patient has fibrolamellar HCC.

Curation Practices for Diagnostic Assertions¶

All Evidence Items relevant to the Assertion should be associated with it, even if they disagree with the Assertion Summary. Disagreements can be discussed in the Description section and rationale for discounting discrepant evidence should be recounted.

The evidence supporting the Assertion should sufficiently cover what is known regarding the diagnostic power for the Molecular Profile in the specific disease context.

For Tier I Level A Diagnostic Assertions, details from relevant practice guidelines should be given, along with any additional specific information which is applicable (e.g., disease stage).

Lower Tier and Evidence Level Assertions may be created for Diagnostic CIViC Variants not currently in practice guidelines. Molecular Profiles backed by stronger clinical data may be Tier I Level B as above. Variants with smaller amounts of evidence for diagnostic potential will receive lower Tiers and Evidence Levels (Figure 4A).

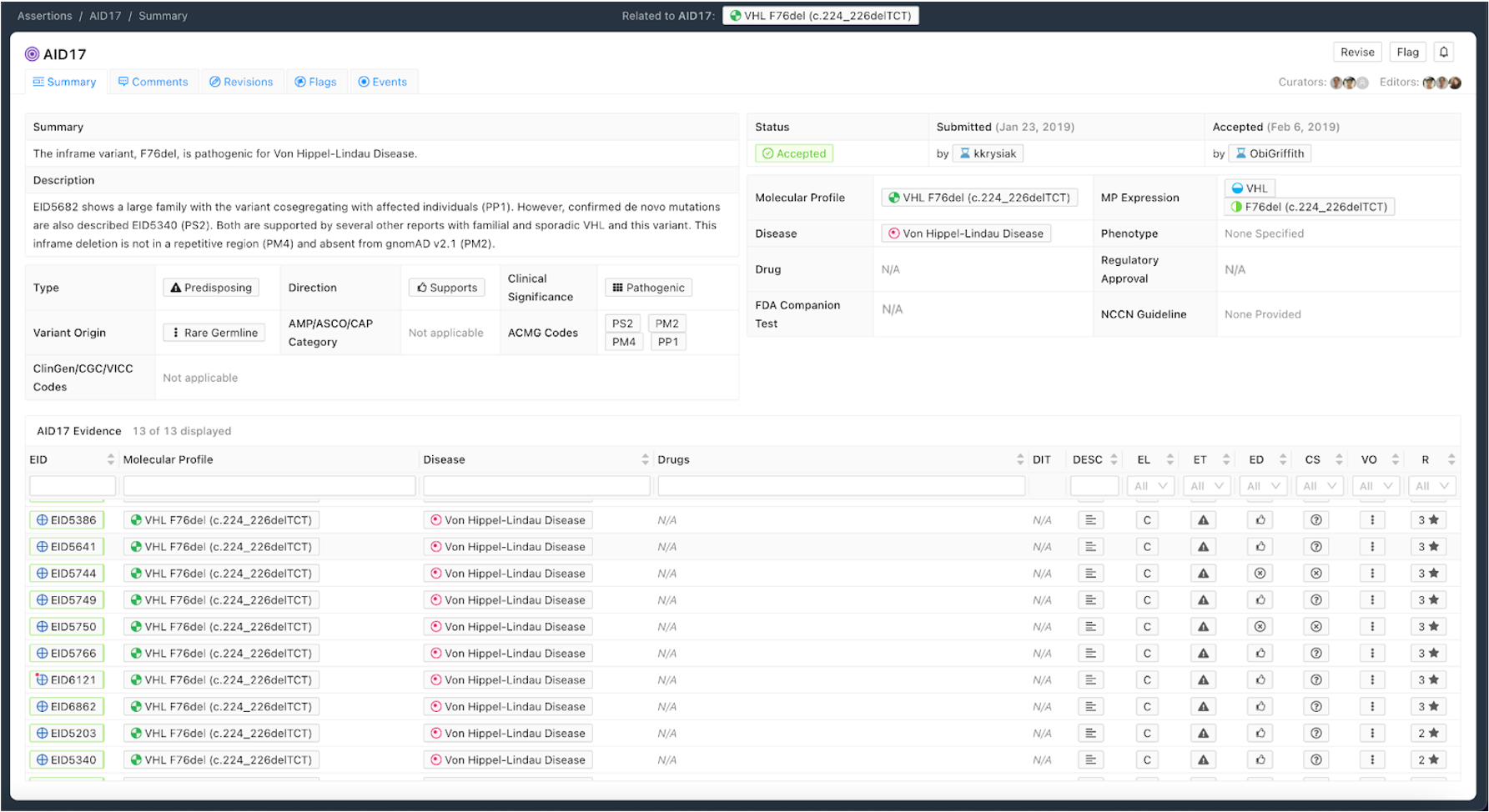

Predisposing Assertions¶

Figure 8 shows an example of a Predisposing Assertion. In this example, an inframe deletion repeatedly observed in the literature is considered pathogenic for Von Hippel-Lindau Disease. Utilizing the ACMG/AMP guidelines [8], evidence codes were assembled from the literature (PS2, PP1) and Variant-level information (PM2, PM4) to be categorized as Pathogenic. Specific evidence is associated with codes in the Description and all evidence evaluated when producing the Assertion is associated with the Assertion.

Curation Practices for Predisposing Assertions¶

ACMG-AMP codes (Richards et al. 2015) supporting the Predisposing Assertion are derived from supporting Evidence Items, and other sources such as population databases (See Figure 4B). Any evidence codes applied should be explained in the Description section, allowing others to rapidly re-evaluate the evidence used.

All Evidence Items relevant to the Assertion should be associated, even if they disagree with the Assertion Summary. Disagreements can be discussed in the Description section and rationale for discounting discrepant evidence should be recounted.

Thoroughly evaluated Assertions can have a Significance of Variant of Unknown Significance (VUS) using ACMG-AMP criteria. This permits other users to quickly re-evaluate this variant in the context of new evidence, potentially leading to reclassification, but reducing future curation burden if the variant is observed again.

Note that currently ACMG/AMP criteria apply to simple (single variant) Molecular Profiles. Multiple ACMG criteria are not forumlated for groups of co-occuring variants accross different genes. For example PM1 (Located in a mutational hot spot and/or critical and well-established functional domain) is not clear wether this would be required of one or all of the variant members of a complex MP. PP1 (Cosegregation with disease in multiple affected family members in a gene definitively known to cause the disease) is also clearly not defined for combinations of varinats. Therefore, the Predisposing Assertion should only be forumlated for simple Molecular Profiles.

Oncogenic Assertions¶

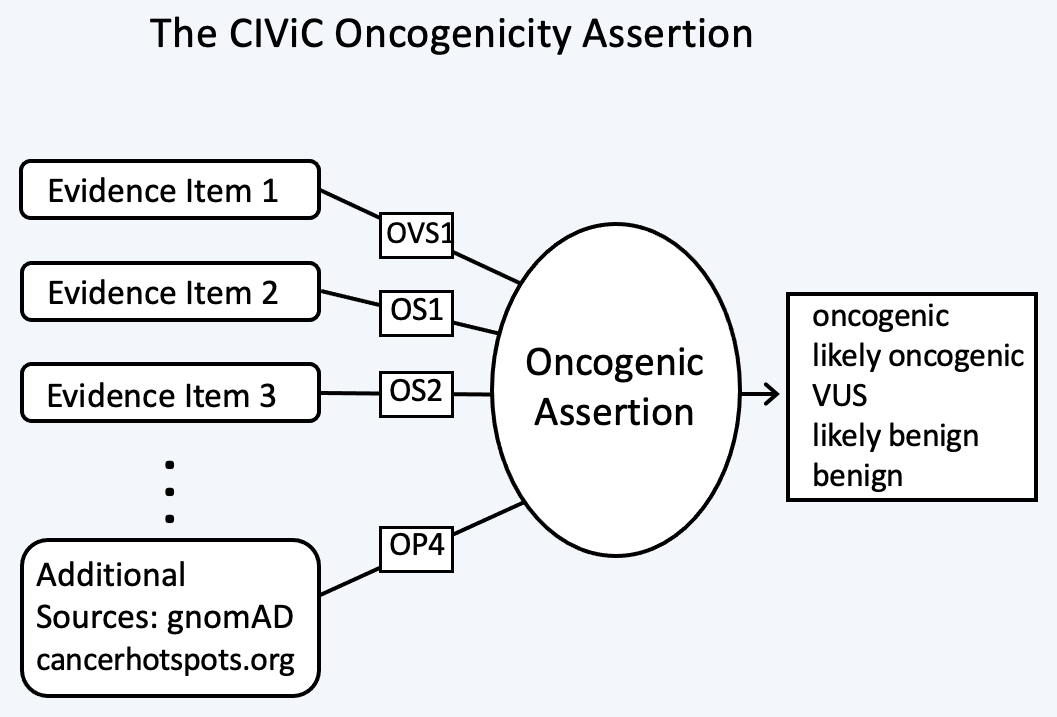

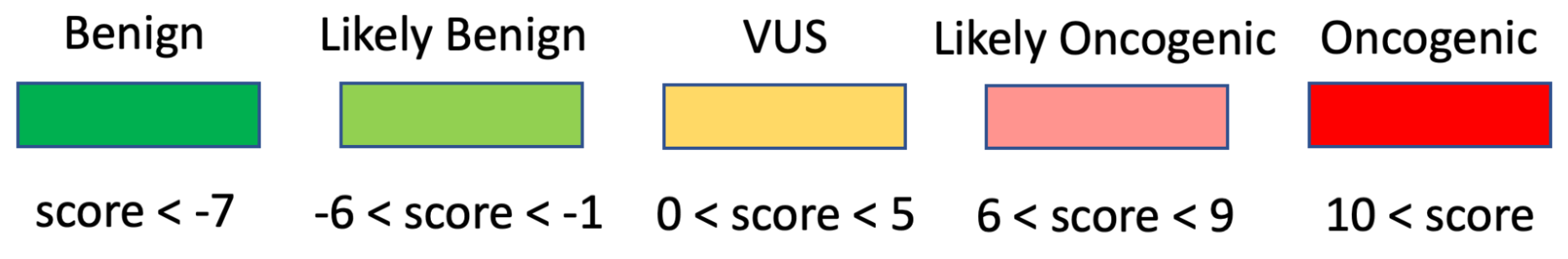

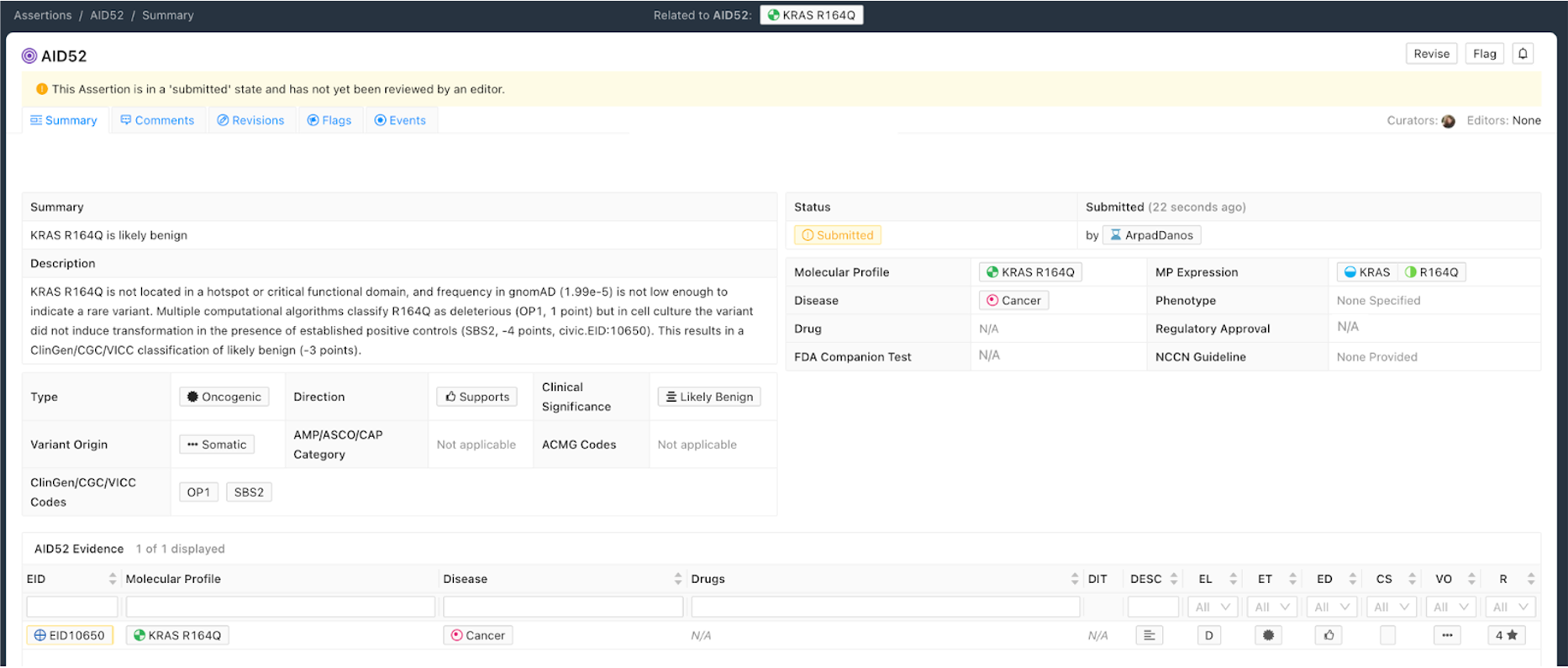

The Oncogenic Assertion (Oncogenic AID) summarizes a collection of Evidence Items (EIDs) for a somatic variant, which together should reflect the state of knowledge in the field for this variant to reach a final oncogenic or benign classification. Oncogenic properties are interpreted as effects induced by the collection of variants which make up the Molecular Profile, that in turn promote one or more of the Hallmarks of Cancer. Benign properties indicate a lack of oncogenic effect for a somatic variant, which ideally will be demonstrated in the context of well defined positive controls. This collection of EIDs can then be summarized into a CIViC Oncogenic Assertion (Figure 9).

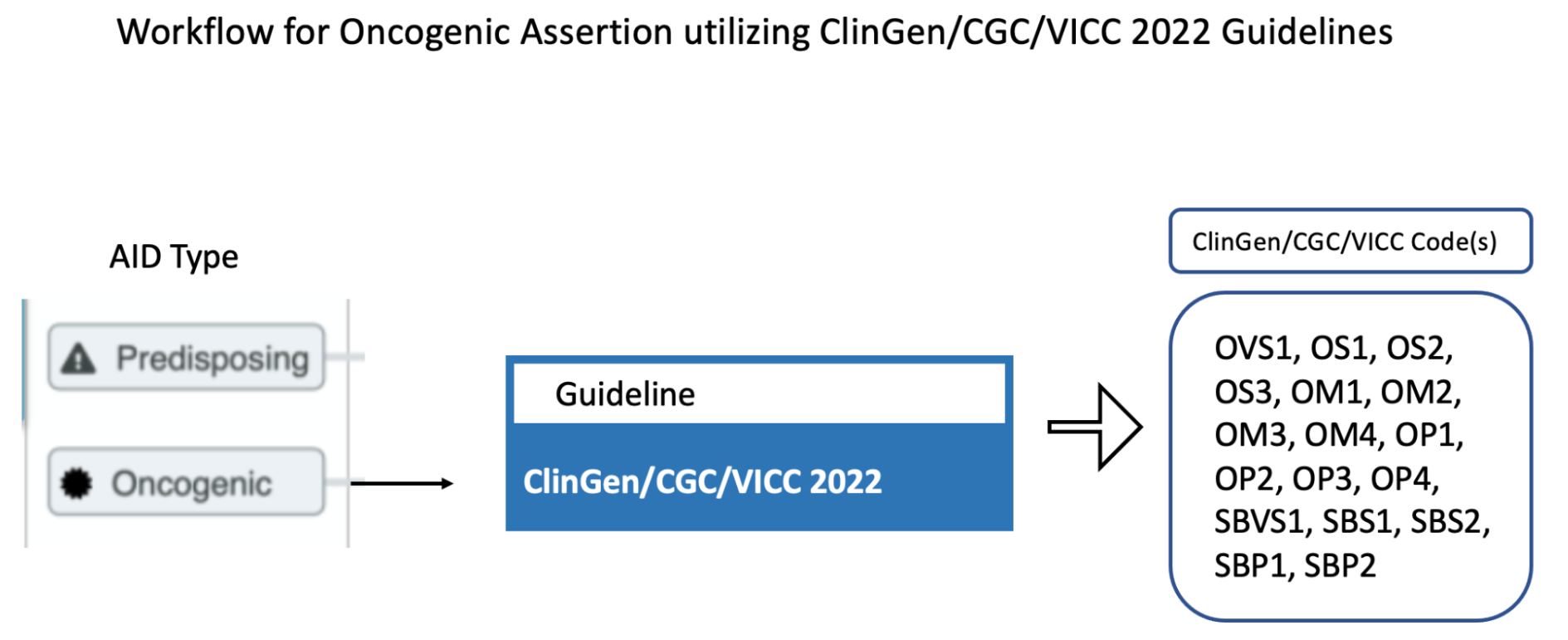

The selection of Assertion Type in CIViC results in a particular choice of variant classification based on the aggregation of evidence codes (Figure 11). For Oncogenic Assertions, after the Oncogenic AID Type is chosen, the ClinGen/CGC/VICC Oncogenicity Codes can be added to the Assertion (Figure 12). This guideline is based on missense and simple insertion/deletion variants, so when curating, only simple Molecular Profiles are used. In some cases, ClinGen Somatic Variant Curation Expert Panels (SC-VCEPs) may choose N/A for evidence code, and instead utilize an SC-VCEP specific protocol for evaluation of oncogenicity. This protocol should be described in the Assertion Summary.

Curation of Oncogenic Assertions requires a brief Summary of the main conclusion of the Assertion. In the Assertion Description the curator should describe generally relevant information about the Molecular Profile’s oncogenic or benign properties, and importantly, describe how the appropriate guideline was used to arrive at the Clinical Significance, which is Likely Benign in the example below (Figure 13). Additionally external information such as population frequencies or data contradictions can be described here. The ClinGen/CGC/VICC Codes are added by the curator in the Add Assertion form, and a brief explanation for each Code used is given in the Assertion Description. For Codes that are derived from Evidence Items, the appropriate Curie link is also added by the curator (e.g., civic.EID:10277). The Disease field is required, and the term Cancer (DOID 162) may be used when the underlying evidence applies more generally.

Note that currently, ClinGen/CGC/VICC criteria are not well defined for complex Molecular Profiles (MPs), and therefore are restrocted to simple (single variant) Molecular Profiles. For example criteria utilizing cancerhotspots or COSMIC data are not well defined for co-occurring variants, as the variant frequencies are only reported for variants in isolation. Therefore Oncogenicity Assertions based around the ClinGen/CGC/VICC guidelines should only be curated for simple MPs. Future guidelines may allow for Oncogenicity Assertions based around complex MPs.

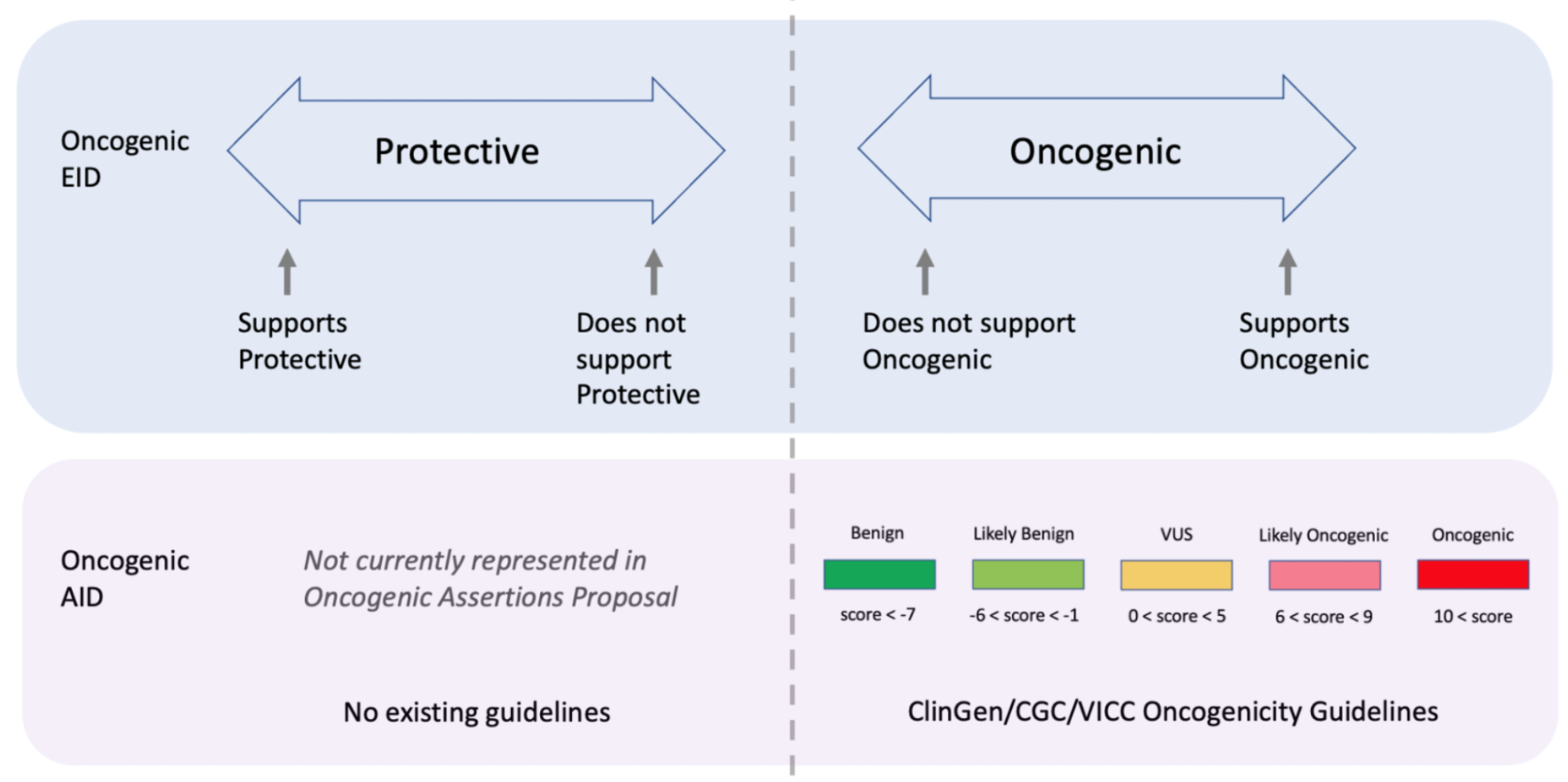

Curators should take note that the Significance of the Oncogenic Assertion (AID) and that of the Oncogenic Evidence Item (EID) do not overlap and instead consist of partially related but different annotations (Figure 14). This also holds for the Predisposing Evidence Item versus the Predisposing Assertion. EIDs provide discrete evidence from a single source and do not represent a final classification, only supporting evidence. The Assertion Significance provides a final classification as a result of the aggregation of information across studies for the variant (Simple Molecular Profile) (i.e., multiple EIDs and other evidence). The Oncogenic EID is set up on two opposing axes describing Protectiveness and Oncogenicity. The Oncogenic Axis is able to capture evidence supporting either a benign or an oncogenic effect for the Molecular Profile (Simple or Complex), but only in rare cases will a single publication or meeting abstract yield enough evidence to obtain a classification of Oncogenic or Benign utilizing the ClinGen/CGC/VICC Guidelines. Because of this, Single EIDs are tagged with Oncogenicity Codes when appropriate, and used to support an overall Assertion (Figure 9). Importantly, note that an Oncogenic EID that utilizes the Protective Significance will have no analog at the level of Assertion. Also note that, currently, only Simple Molecular Profiles (single Variant) are supported for Oncogenic or Predisposing Assertions as the corresponding guidelines were not designed for Complex MPs.

Citing EIDs in Assertions¶

As described above, EIDs supporting the Assertion’s clinical significance may be listed in Assertion description, and referenced using CURIE identifiers (e.g., civic:EID1234). However, there is no simple/specific answer for how many and which EIDs to cite. It varies with the AID type and complexity. Curators should use their judgement but consider citing EIDs as similar to citing supporting works in a scientific publication. The following suggestions may help:

Do not simply cite all EIDs (they are already associated with the AID). Cite specific EIDs that will help editors or eventual readers of the assertion. Focus on strategic citations that help the end user.

The practice of strategically citing a few EIDs may be more useful where there is a larger number of EIDs associated with an AID, but not as critical if there are only 1-3 EIDs.

Examples of situations where you might want to cite specific EIDs in an AID include:

If certain EIDs support specific aspects of the assertion (particularly when describing support for specific standard evidence codes)

To draw extra attention to EIDs that are considered particularly critical or high quality.

When describing specific nuances, contexts, controversies that might influence interpretation of the EID.

When there is a heterogeneous mix of evidence supporting an overall assertion. For example, there are 10 EIDs. Some correspond to functional data, to case reports, and clinical trials. Maybe cite 1-2 key EIDs for each of these evidence types.

When evaluating evidence in the context of a guidelines (such as oncogenicity SOP or Fusion oncogencity SOP), it is often the case that evidence is found to support 4-5+ distinct evidence lines. If these are drawn from 15-20 evidence items it can be a lot of work for the reviewer to figure out which EIDs support which codes.

From a stylistic perspective, we anticipate that a short assertion will typically refer strategically to at least 1-2 EIDs. A longer assertion might have more.